Interpreting Hypocitraturia: An Etiology First Approach

- Viresh Mohanlal, MD

- Nov 11, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: 1 day ago

As a nephrologist, I frequently see patients with kidney stones, and one finding that appears with striking regularity on metabolic evaluations is hypocitraturia, defined as urine citrate <320 mg/day. In large-scale urine studies, hypocitraturia is now the third most common metabolic abnormality in stone formers, surpassed only by high urine calcium (>250mg/day) and low urine volume (< 2 L/day), significant risk factors for kidney stone formation (1).

Over the past two decades, the prevalence of hypocitraturia among patients with calcium nephrolithiasis has increased from approximately 20% to nearly 60%. During the same period, nephrolithiasis in the United States has nearly doubled, affecting approximately 8–9% of the population(2). These increases have occurred alongside rising rates of obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome, suggesting a common underlying etiology. Poor dietary patterns with high salt, processed foods, and animal protein intake, combined with low physical activity, have contributed to obesity and metabolic syndrome. These metabolic changes, in turn, reduce urinary citrate excretion and increase the risk of kidney stone formation.

Citrate is the main organic acid found in urine and helps prevent calcium-based kidney stone formation by inhibiting the nucleation, growth, and aggregation of calcium crystals. Citrate also acts as a base equivalent for alkali excretion and plays an important role in maintaining a stable urine pH. Approximately 10–35% of the freely filtered trivalent citrate (citrate3+) is excreted in the urine and is regulated by the activity of sodium dicarboxylate cotransporter (NaDC-1) located on the apical membrane of proximal tubular cells (3). The vast portion is reabsorbed in the proximal tubule after it is converted to the divalent form (citrate2+) through luminal hydrogen ion (H+) titration. This process involves the apical sodium–hydrogen exchanger (NHE3) and the uptake of citrate2+ via NaDC-1 (4). After reabsorption,citrate2+ is metabolized either in the cytosol, where citrate lyase converts it into acetyl-CoA or oxaloacetate, or in the mitochondria, where it enters the Krebs cycle. Citrate metabolism generates bicarbonate, which is returned to the circulation via the sodium–bicarbonate transporter (NBCe1a). (Figure 1).

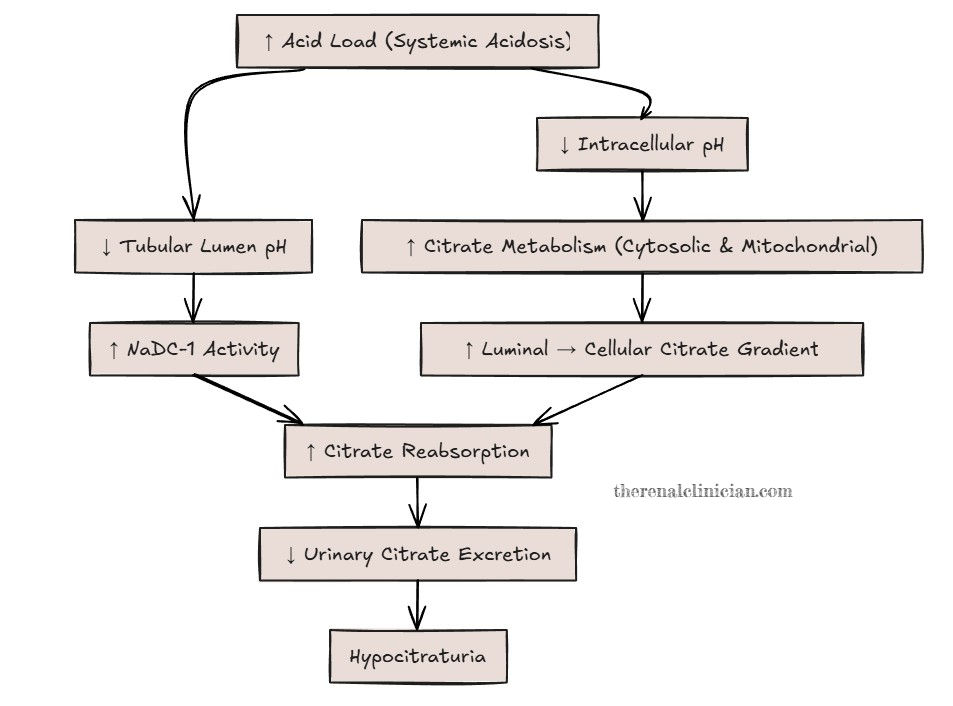

Acid–base balance and potassium status are key determinants of how much citrate the kidney reabsorbs or excretes (5). When the body is exposed to a higher acid load, as with metabolic disorders, obesity, and the standard American diet high in animal protein and processed foods and low in potassium-rich fruits and vegetables, the kidneys adapt. Increased acid load stimulates NaDC-1 activity in the proximal tubule, enhancing reabsorption of citrate2+. At the same time, changes in intracellular pH promote citrate metabolism through cytosolic and mitochondrial pathways, creating a stronger luminal-to-cellular gradient that favors further citrate uptake. The result is lower urinary citrate excretion (Figure 2).

Data from male and female kidney stone formers evaluated in the Mineral Metabolism Clinic at UT Southwestern Medical Center(1975-2010) showed an inverse relationship between urinary citrate and net dietary acid load (urinary sulfate- urinary K), estimated by urinary sulfate (a marker of acid excretion) minus urinary potassium (a marker of alkali intake). As net acid excretion increases, urinary citrate falls, highlighting how acid loading promotes hypocitraturia rather than reflecting a primary citrate defect (Figure 3).

Potassium depletion has a similar effect. It leads to intracellular acidosis and increased hydrogen ion secretion via NHE3, which increases the formation and reabsorption of divalent citrate. Again, urinary citrate falls (6).

In this context, reduced citrate excretion is not an inherent defect but a physiologic response to chronic net acid load. Current dietary habits, characterized by high intake of meats and processed foods and low intake of potassium-rich fruits and vegetables, create a persistent acid burden. The resulting hypocitraturia often reflects this dietary pattern. While this adaptation may increase the risk of calcium stone formation, it is fundamentally driven by the underlying acid load.

Yet in current practice, many kidney stone patients are started on potassium citrate simply because their urinary citrate falls below an arbitrary cutoff. Medicare Part D data indicate that potassium citrate use for the treatment of hypocitraturia increased by 56% from 2013 to 2020. Too often, the number is treated rather than first addressing the dietary acid load, metabolic contributors, or potassium deficiency that drives hypocitraturia.

Potassium citrate has a clear role in selected patients. However, when hypocitraturia is an appropriate physiologic response to chronic dietary acid load, the first step should be to correct the underlying cause rather than simply correcting a laboratory number. Before prescribing potassium citrate, it is essential to identify modifiable factors contributing to low urinary citrate. These include low urine volume (<2 lts/day), high sodium intake (urinary sodium >150 mEq/day), medications such as thiazides, loop diuretics, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, and topiramate, high animal protein intake (protein catabolic rate >1 g/kg/day or urinary sulfate >60 mEq/day), and low potassium intake (urinary potassium <60 mEq/day). If these factors are not identified and corrected, the underlying acid load persists, and the risk of kidney stone formation remains, even if citrate levels improve (7).

During the next metabolic evaluation for kidney stones, consider reviewing and addressing dietary acid load before prescribing potassium citrate. Making this a routine part of practice can help ensure underlying etiologies are addressed and guide more targeted therapy.

References:

Ferraro, P. M.; Taylor, E. N.; Curhan, G. C. 24-Hour Urinary Chemistries and Kidney Stone Risk. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2024, 84 (2), 164–169

Alibrahim, H.; Swed, S.; Sawaf, B.; Alkhanafsa, M.; AlQatati, F.; Alzughayyar, T.; Abdeljawwad Abumunshar, N. A.; Alom, M.; Qafisheh, Q.; Aljunaidi, R.; Mosleh, O.; Oum, M.; Bakkour, A.; Barakat, L. Kidney Stone Prevalence among US Population: Updated Estimation from NHANES Data Set. JU Open Plus 2024, 2 (11), e00115..

Hamm, L. L. Renal Handling of Citrate. Kidney Int. 1990, 38 (4), 728–735.

Hering-Smith, K. S.; Hamm, L. L. Acidosis and Citrate: Provocative Interactions. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6 (18), 374.

Zuckerman, J. M.; Assimos, D. G. Hypocitraturia: Pathophysiology and Medical Management. Rev. Urol. 2009, 11 (3), 134–144.

Hamm, L. L.; Hering-Smith, K. S. Pathophysiology of Hypocitraturic Nephrolithiasis. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2002, 31 (4), 885–893, viii.

Zomorodian, A.; Moe, O. W. Citrate and Calcium Kidney Stones. Clin. Kidney J. 2025, 18 (9), sfaf244

.png)

Comments